FALL/WINTER 2025

Taylor Swift's Reputation

Stephanie Burt

The run-up to Reputation featured a gambit that few stars could pull off: On Friday, August 18, 2017, Swift’s social media went dark, all posts gone or hidden. The following Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, her official Instagram added one, two, three videos of a cobra, followed by the first single, “Look What You Made Me Do.” Then came the album announcement: “Reputation: The new album from Taylor Swift. November 10.” More snakes popped up in the album’s rollout: As Sarah Chapelle has noticed, the Gucci sweatshirt Swift wore that year on Saturday Night Live replicated “the crisp red, black and white stripes of a scarlet kingsnake.” The Reputation tour kept the ophiology going, bringing on stage a sixty-three-foot inflatable cobra named Karyn. What makes that kind of snaky behavior relatable? Few among us have faced the level of tabloid opprobrium that comes with the life that Taylor, after 1989, led. Many of us, though, have seen cancellation online; have faced libel or slander on social media, as well as within a friend group; have felt pursued by unchosen drama; have felt enmeshed in gossip that singles us out. “This is how the world works,” Taylor muses, almost under her breath, in “I Did Something Bad”; and, in “End Game,” “I don’t love the drama, it loves me.” If going after her once looked like stepping on a puppy (as Katy Perry put it back in 2009), now it meant waking a snake. Everything that hurt or cramped or pained her about her celebrity persona, all the allegations and the lame, would become her new material.

Reputation became in that way a fifty-five-minute, forty-five second course in inspirational reputation management. It also showed Taylor, for the first time (unless you count the sarcastic persona of “Blank Space”), portraying a grown-up menace, acting like someone you might not want your kid to know. She wrote songs about lust, intoxication, and parties, “whiskey on ice” and “Sunset and Vine,” in the ancient genre that lit-crit types call Anacreontic (after the Greek poet Anacreon, who wrote drinking songs), a genre represented best these days in Black pop and R&B. The Taylor of Reputation also adopted another classical genre, the apologia, in which someone defends their life and their actions—not a way to say, “I’m sorry,” but a way to explain why they did what they did.

That’s one reason Reputation embraces, as 1989 had not, the textures, timbres, and building blocks of modern hip-hop, as well as 2010s R&B. The album includes, also for the first time, phone calls, found sounds, and other nonmelodic interludes: normal on rap and R&B albums, rare in rock and country. The old Taylor can’t come to the phone right now (because she’s dead). The new Taylor might be thinking (for example) of the phone call at the end of Brandy’s “Full Moon” (2001), or of Drake’s “U With Me?” (2016). Reputation relies almost throughout on the track-and-hook songwriting that Taylor introduced, sparingly, on Red, where one creator makes beats and another makes lyrics and melodies. Unusual in rock and country, that method has become standard in R&B, in rap, and in dance pop, like the kind that Calvin Harris and Rihanna made. Swift and Harris even cowrote Rihanna’s “This Is What You Came For,” whose stretched-out version of “you” (up to ten syllables at the end of the chorus!) matches its dance-all-night vibe, while its cleverly minimal lyrics describe their own function: “We say nothing more than we need.” Swift appeared in the songwriting credits as “Nils Sjöberg,” apparently so as not to upstage Harris.

The bounty of Sweden notwithstanding, the method points back to Black America. Making an R&B album, Swift not only chose “the coolest, most creative” genre around as of 2016 (as Kelefa Sanneh put it in his book on genre); she chose a genre that (in Sanneh’s words) “can never quite decide whether it wants to be the universal sound of young (and not-so-young) America, or Black people’s best-kept secret, or—somehow—both at once.” Of course, it cannot manifest both at once, and yet that’s the antinomy Swift wants to invoke. If she can’t make the two things into one thing, maybe she can make, at the least, the sound of escape from a white-coded hypocrisy, the supposed white innocence of the alleged Aryan sweetheart, the paleness of Taylor Swift’s past.

That rejection began with track one. Caroline Sullivan calls “…Ready for It?” the first track in Swift’s career where she presents herself as a “sexual aggressor.” That track layers processed vocals over trap beats and a whomping subwoofer: Similar hi-hat effects crop up throughout the album, as Taylor creates some distance between her present-day, dauntlessly embodied, unhindered self and the girl she no longer wants to be. Other love songs on Reputation let Taylor sound naughty, openly seductive, no longer chasing a teenage dream of forever and always, but instead inviting her partner into a risky situationship, with bedroom eyes. Swift paints herself as the thief in the “getaway car,” as the larcenous betrayer, as the captive who can escape (“Dancing with Our Hands Tied”). “End Game,” with Future and Ed Sheeran, nearly suggests that she’s dating two people at once, “drinking on the beach” with at least one of them, as she puts it, “all over me.” It’s a classic seduction song, living in the moment, with its booming electronic drum hits and trap beats, as if to say that she doesn’t regret what the world made her do. “King of My Heart” too, with its clicking, buzzing, booming sequence of rhythm tracks, picks up on what Swift learned from modern hip-hop. Early in the song she half-speaks, half-sings over finger-snaps. By the time she sings the title in the chorus, she’s multitracked and Auto-Tuned. Post-chorus segments bring in, of all things, a drum line. This version of Swift may have tired of fancy cars, but she’s willing to put the textures of her new romance up front, asking that we see ourselves in this newly infatuated, somewhat jaded adult.

*

Swift’s choices —in lyrics, in music, in self-presentation— throughout Reputation, as they invoke her whiteness, and other musicians’ Blackness, leave her open to serious moral objections. If the way out of white innocence and racialized, helpless, desexualized girlhood involves learning from (or appropriating) Black sounds, what does that choice say about Blackness? Has the Swift of Reputation, of “Dress” and “End Game,” played into stereotypes she hoped to escape by reinforcing other stereotypes, namely the racist idea that Black people, even young ones, are hypersexual, dangerous, prematurely adult? If whiteness means innocence and vulnerability, what does it say, what stereotypes get reinforced, when the way to hit back is to start sounding Black?

Reputation looks, from this point of view, like one more example of the centuries-old phenomenon that Toni Morrison’s Playing in the Dark—and many later critics—have described. Swift becomes one more of the many white artists relying on Blackness, Black sounds and Black people, to represent something scary, repressed, or hard to name in our white selves. Certainly there’s something alarming about an album, or a person, or a culture—American culture—that associates whiteness with harmlessness, and Blackness with confrontation. That association, put in practice by law enforcement, gets Black people killed. At the same time it feels like a stretch to blame Taylor Swift’s choice of drum-machine patch for those killings.

A defense of the racial politics in the sounds of Reputation—a defense I find as plausible as (though no more so than) the critique—might say that hiving off certain kinds of fears, fantasies, threats, and “adult” ideas from others, and then projecting them onto Black people, onto Black characters, is exactly what Reputation does not do. Instead, the enticing textures of R&B, the collaborative (and still confrontational) ethos of modern rap, turn out to fit not some invented, ventriloquized, or appropriated Black character, but Taylor Swift herself. [Disclaiming and refusing the musical fantasies of whiteness bound up with the styles that her earlier records deployed, Swift, and her coauthors and collaborators, from Max Martin to Future, went to the music they saw as powerful, helpful, and less constrained. They worked to learn. They showed (knowingly or not) how white-coded musical styles and resources can render invisible, or fail to register, white people’s emotions. And Swift did these things, from “... Ready for It?” to “This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things,” without attempting to speak for, or from, Black life. In this sense she did try to stay in her lane.] Like every other product of white America, she must learn to listen to Black culture and Black-coded art forms so that she can recognize, and honor, the rejected, ignored, suppressed, bracketed parts of herself. White people, white artists, should stop—as soon as possible, and almost however possible—assuming we’re the heroes, the innocents: We need to get off our white horse.

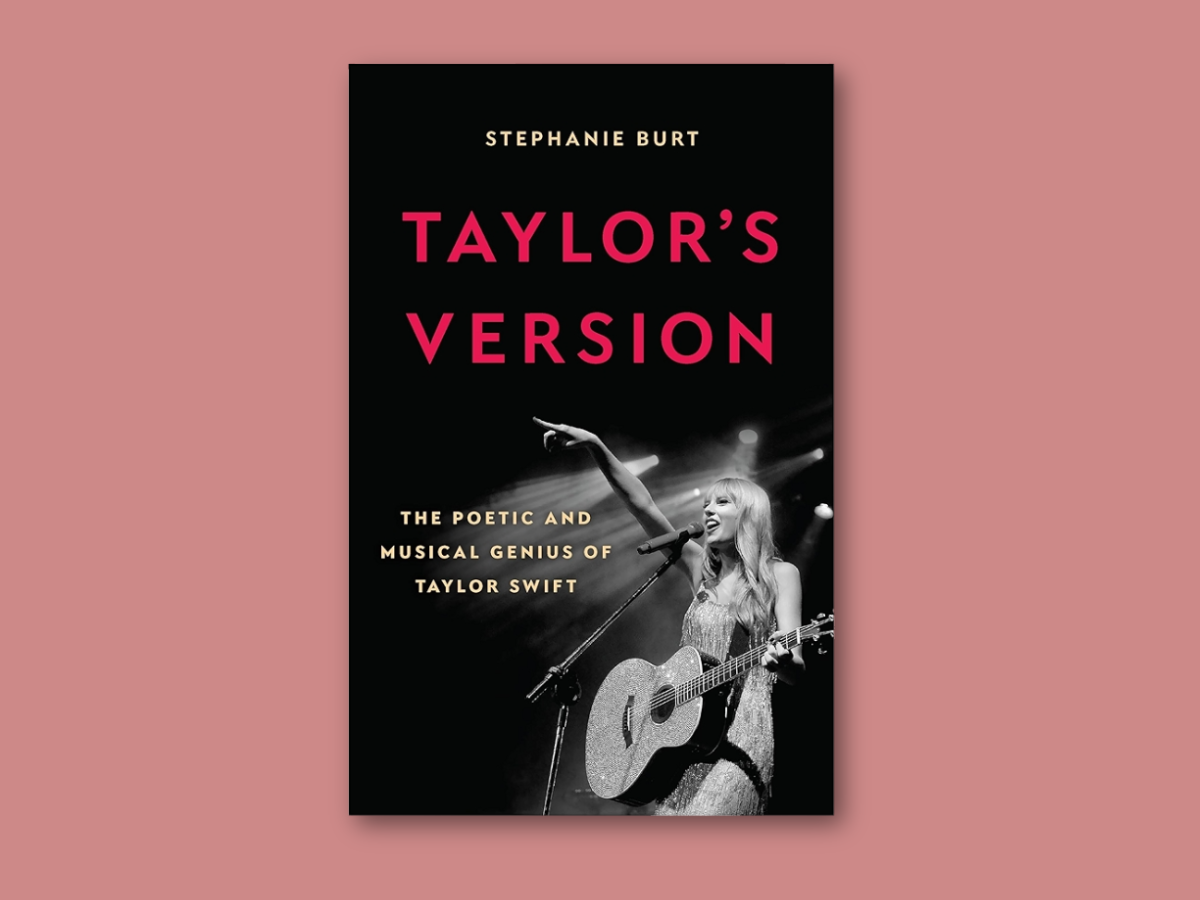

Excerpted from Taylor’s Version: The Poetic and Musical Genius of Taylor Swift by Stephanie Burt, copyright © 2025. Used with permission of Basic Books, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.