FALL/WINTER 2025

Three Variations on Vision

Jean Frémon

Translated by Cole Swensen

The World out the Window

Bonnard at the Louvre with Jean Leymarie, lingering before his favorite paintings, saying nothing, but also stopping in front of each window that looked out on the Seine. As they left, he said, "The best thing in a museum are the windows."

Seen through a window, a landscape is no longer nature, raw and infinite; an order has been imposed upon it. It is framed. It becomes a plane, a truncated cone. The tree is cut out against the sky; verticals and horizontals echo each other, and from the part to the whole, proportions surge, giving rise to a rhythm, a song. It's the desire for a painting, a desire not yet disappointed by the ultimate inadequacy of all ability or the lack of it. A landscape out a window is already an image that seems to want nothing more than to be painted.

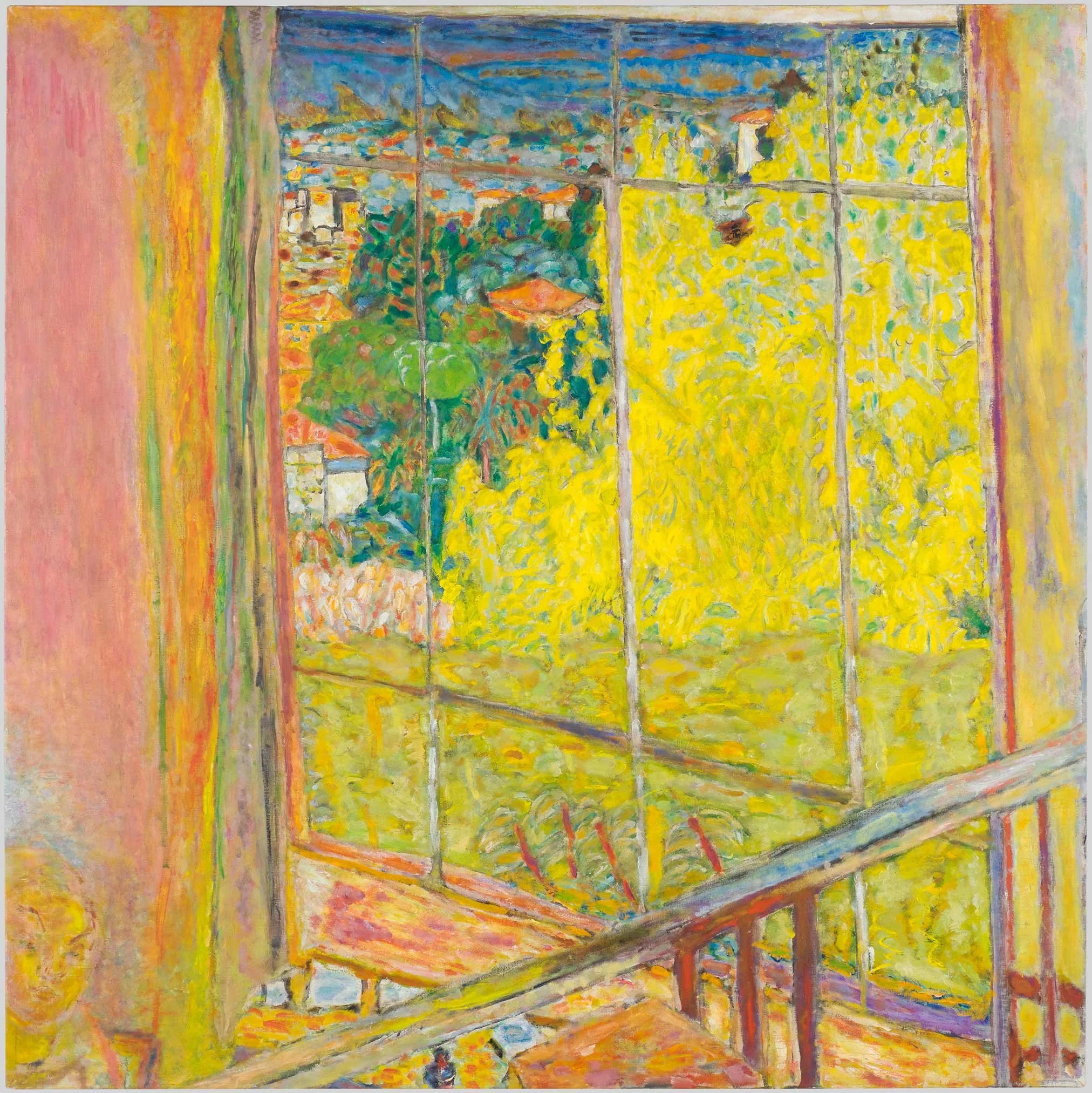

Pierre Bonnard, The Studio with Mimosas.

What was Monet looking for in Rouen from the window of the fitting room at Fernand Levy's, merchant of novelties, or that of Louvet, the tailor, or that of the shopkeeper Mauquit, in the rue Grand-Pont? The cathedral is there, truncated, overwhelming the entire frame. Neither the street nor the square is visible, nor are the tops of the towers or the spire, and only a tiny corner of sky. The cathedral floats; it's in mid-air. Its base is the windowsill, the edge of the painting. And is it therefore still a cathedral? It's sculpted stone, vibrant, its angles dazzlingly catching the light, but it's also simply a rectangular surface, a picture in which every luminous point requires only to be replaced by a touch of color. It's a huge wave, sonorous, abstract, fluid, vaporous, polyphonic, Wagnerian.

Though don't think, because I've used the words simply and replaced, that it's just a matter of following a formula. No, it's a relentless duel. And the windowsill is the field of action.

Like the window, the mirror has the virtue of bringing reality half-way to the painting. In a mirror, the third dimension is already an illusion, trapped in the silvering. This illusion captures the mind, and it only needs another—perspective—to reconstruct within the space of the canvas the depth that the mirror has tamed.

The Monkey of La Grande Jatte

Georges Seurat was a methodical man. He pretty much thought of painting as a science, and one doesn’t argue with the principles of a science. First principle: before composing, observe. To compose is to create a relationship among forms, lines, and masses, and to organize them into a painting. But these forms are always very carefully and faithfully borrowed from observed reality. Nature is a dictionary; you find words there, and then you must make a poem.

For La Grande Jatte, he planned to put the boat on the branch of the Seine in the foreground, but the grass had grown on the banks and had masked it. That’s intolerable, he thought; I need that boat; without it, the whole thing won’t work. But I have to see it from this angle—as seen from the bridge, it’s a different boat. His friend Charles Angrand, who told the story, offered to cut the grass so that the boat would be visible again, which Seurat, in his final composition, refused, perhaps finding the reality with grass superior to the reality without grass.

Another day, he saw a woman strolling with a small monkey on a leash walking on all fours through the grass. What luck—after several quick sketches, the animal was worked into the picture. A wonder of curves in perfect balance, the small acrobat, with his long tail like a balancing pole, lent his lightness to the whole. He was joined by a yapping poodle borrowed from another stroller.

Two years passed, and some twenty drawings and thirty small oil sketches accrued before A Sunday Afternoon on the Ile de la Grande Jatte was finished. A Sunday made of a hundred and four Sundays and six hundred and forty other days. The day of the hat, the day of the parasol, the day of the sailboat, the day of the rowers, the day of the pipe, the day of the man with the top hat, the day of the light in the grass, the day of long shadows. The simplicity of the forms and the hieratic relationships of the characters are nothing but the synthesis of thousands of observed details.

Two years earlier, The Bathers had been refused at the 1884 Salon. Pissarro managed, despite igniting controversies among its members, to get Seurat admitted to the Eighth Impressionist Exhibition in the rue Laffitte, and Seurat sent his A Sunday Afternoon on the Ile de la Grande Jatte. Laughter and mockery. Some saw in the foreground a reclining jockey who’d lost a leg jumping hedges, but what caused unanimous derision was the monkey held on a leash by the lady in blue. Total farce, wrote one journalist. A monkey, just think …

Distancing himself from his rare admirers, Seurat said, “They see poetry in what I do, but no, I apply my method, and that’s all.” And as for method, there’s no fooling around with it. Monkey in nature, monkey in the painting.

Georges Seurat, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.

The Man Who Did Portraits of Mountains

A retired spot untouched by the agitation of the world. A village of stone and wooden houses with steep roofs, of small, narrow streets rising toward the first fields on the hillsides, and mountains suddenly soaring up to the sky from both banks of the river that runs along the road. The river, in summer, a chaos of brilliant water jostling over large round stones, is, in winter, a flat sheet of ice. The Val Bregaglia is so narrow that during the three months from late autumn through winter, the sun never touches the bottom of the valley. When it shines at all, you have to be content with watching the rays cut across the peaks. They do it as if with a scalpel, the light is so precise at that altitude. Alberto Giacometti never tired of the spectacle. The white stone bed of the Mera, the granite rocks, like blocks of the unknown, between the trees, in the middle of the fields. As a child, he had an affair with one of those rocks. I say affair as one might speak of a romantic encounter. Can one fall in love with a rock? Why not? It was a large golden rock, twice as high as he, sitting there, across the slope. Since when? Running waters had carved around its base, creating a small cavern, into which the child managed to slip, remaining there crouching. The stone was his friend, a being who wished him well.

In the chapter of mineral encounters, there’s another that’s not so pleasant. One day when he was wandering alone in the hills, he found himself on a kind of promontory, and he saw down below, in the brush, an enormous black stone in the shape of a pyramid, narrow and pointed, planted in the earth. He immediately sensed that this stone was hostile and menacing. Feeling guilty, he approached it, but decided not to mention it to anyone. He managed to ignore it, but not to forget it, and many years later, he recounted the memory, which haunted him still.

A 1933 work titled The Table shows a table that has four different legs, and placed on it, the half-veiled bust of a woman and an open hand. The wide eyes, the parted mouth, and the gesture of the hand all suggest a stunned response to the strange polyhedron positioned on the corner of the table. And several months later, in 1934, the surprising sculpture known as The Cube. It’s not a cube at all; it’s a form very similar to the polyhedron of The Table, though greatly enlarged. Its crisp edges and multiple faces, each reflecting the light differently according to their position, create a being apart, mute, closed in on itself, forcefully recalling the persistent memory of the menacing black stone of Maloja.

Many years later, after the war, he dropped symbolic and allegorical forms in an attempt to stay closer to reality, focusing above all on portraits. From memory or based on a model, he did heads and busts of his brother, his wife, and a few rare friends, in clay, plaster, paint, and pencil, endlessly seeking a resemblance that seemed to flee him. How did this man, who spoke of nothing but resemblance, who claimed to have no other care in his life but to understand what he saw and to copy whatever was before him—which, as his work shows, he could do brilliantly—always end up with works graced by every quality except precisely that of truly resembling their models?

What they resemble most, these walking men, these standing women, these heads, these busts, this arm, this leg, this dog, is not Diego, nor Annette, nor Caroline, nor Éli, nor any dog, but the peaks and crests seen when looking up at the sky behind the roof of his childhood home in Stampa, a village isolated from everything, to which he returned to die and which bears his mother’s maiden name.